Dynamic Memory Allocation Part1

by Mike Krinkin

In the previous post I mentioned that I implemented simplistic dynamic memory allocator and plugged it into Rust. So I thought I could create an introductionary post into dynamic memory allocation algorithms.

This post will cover a basic algorithm of dynamic memory allocation and some practical aspects that we might consider when implementing dynamic memory allocators as a sort of introduction into the problem (thus Part1).

As always the code is available on GitHub.

Motivation

Since it’s a sort of an intrdouction post it worth briefly covering why do we need dynamic memory allocation at all. Ignroing for a moment low-level part of software systems and their special needs and goals, let’s consider regular user-space binaries. In such case we can potentially statically reserve the maximum amount of memory the problem could potentially require and then use that statically reserved memory.

Statically reserving memory basically means recodring how much memory the OS should give to the program when loading the binary in the binary itself.

NOTE: I’m simplifing a lot here by not considering how OS would give memory to the program in the first place, not to mention that I’m leaving aside a case when there is no OS at all. However static memory reservation is still quite different from the dynamic memory allocation in the sense that all the memory allocated upfront and not freed until the end of the program.

If we take, for example, a classic Unix utility sort, that by default

just sorts input strings lexicographically. We can say that it only makes sense

to use this utility if we process no more than XGiB of data and reserve that

much. The value of X might depend on multiple factors, but I’d say there is

always some limit beyond which using a particular tool implementation isn’t

practical anymore.

So all-in-all reserving memory statically should be possible, so it should be possible to live without dynamic memory allocation. However, as you could have noticed the fact that it’s possible, doesn’t mean it’s convenient.

For our sort tool case, the limit X might depend, for example, on the

available amount of RAM in the system or a particular model of CPU. That would

mean that we might need to rebuild the sort tool for all those different

hardware configurations - which is, as I pointed before, isn’t particularly

convenient.

Argument of convenience is far from being a universal one. It’s open to subjective interpretations and various unclear tradeoffs. Moreover the importance of convenience depends on the problem. For example, The Motor Indiustry Software Reliability Association (aka MISRA) C language guidelines prohibits the use of C dynamic memory allocation because of the safety concerns.

Are there more objective arguments for/against of dynamic memory allocation? Let’s return back to the problem of sorting. One of the classical sorting algorithms is Merge Sort.. A typical Merge Sort implementation of arrays would depend on a temporary buffer of \(O(n)\) size. This buffer is only needed during the sorting and is not used for anything else, however regardless of that we’d still need to reserve memory for that buffer.

Such temporary buffers that are only used sometimes, depending on the specifics of the program, may add up to a noticable memory footprint and inneficient memory usage. So you might want to consider reusing the same memory for different purporses in the program. Or, in other words, you might want to consider using memory pooling and create methods to request memory from the pool and return it back when it’s not needed for somebody else to use. It looks just like dynamic memory allocation problem. isn’t it?

Whether your particular case benefits from pooling or not depends on the program of course. The main point of the argument though is that benefits of memory pooling might be objectively measured.

The final argument for the dynamic memory allocation that I would like to touch on here comes from resuing code. Many programming languages come with a sort of standard library. Frankly, even if they didn’t somebody would create such a library anyways. Quite often standard libraries include various collection implementations (vectors, linked lists, various sets and maps, etc).

Statically reserving memory for those in the library is rather problematic. The same library can be used in multiple different environments with different constraints and requirements. If we want to be able to reuse those libraries between different environments, memory reservations has to be abstracted somehow. Dynamic memory allocation is one way to achieve that.

Dynamic memory allocation interface

Now when I’m done pouring the water we can move towrads more practical matters. What interface should dynamic memory allocator have? Actually, there isn’t a universally accepted correct answer for that question.

The question of the right interface isn’t just a question of conveince for the users. Some interfaces may prohibit certain implementations. As a result we might want to consider multiple different interfaces. I start from a relatively minimal interface:

#include <stddef.h>

void *allocate_memory(size_t size);

void free_memory(void *ptr);

The names of the functions might be self explanatory, but nevertheless let’s

spare a few words to explain them. allocate_memory reserves a contigous

memory range of size at least size bytes and returns the pointer to the start

of that memory range.

NOTE: Naturally, it may happen that the dynamic memory allocator cannot find a large enough contigous memory range to satisfy the request. In this case the function would have to indicate a failure somehow. Typically a

NULLvalue is used to indicate a failure, but it’s ok to change interface if returningNULLvalues is somehow not to your liking.

free_memory performs a revese operation. It takes a pointer returned from

allocate_memory function and marks the reserved range as free and available

for allocation again.

This interface assumes that we will be able to derive all the information we need to free the previous allocated memory range from the pointer to that memory.

It might look like a non-trivial requirement, however it’s not that

significant. Basically when allocating memory inside allocate_memory we can

reserve slightly more memory than requested. In this additional memory we can

store whatever metadata we want. This way we could easily discover the

information we need from the pointer passed to the free_memory.

It’s not to say that this caveat will not make the implementation harder, it will most likely add a bit of complexity to the implementation. However it’s not fundamental to the dynamic allocation problem itself.

NOTE: C standard requires its

freefunction to acceptNULLpointer. That’s curiously simmetrical:freefunction can accept any pointermallocand company can return, even if they failed.

To the two functions above I’d like to add one more function:

void add_memory_pool(void *begin, void *end);

This function will serve a purely techincal reason. It will tell the dynamic memory allocator what memory it has available in the system to begin with. With this function we don’t need to discuss how do we find what memory is available and what memory does the dynamic memory allocator can distribute. Those are important questions, but they have very little to do with the actual dynamic memory allocation algorithms.

NOTE: potentially we can add multiple memory pools to the memory allocator. It will hardly change anything in the algorithm I will be discussing, but it might be quite important from practical point of view.

While discussing the interface it’s worth saying a few words on the correct

and incorrect usage of the interface. I will assume here that allocate_memory

and free_memory can only be called in pairs: for each free_memory call

there must be exactly one allocate_memory preceding the free_memory call

that returned the pointer passed to the free_memory call as an argument.

Let’s look at a few examples. Here is the correct example:

void *ptr = allocate_memory(size);

free_memory(ptr);

A slightly more complicated, but still correct example:

void *ptr1 = allocate_memory(size1);

void *ptr2 = allocate_memory(size2);

free_memory(ptr2);

free_memory(ptr1);

In the last example without losing correctness we can change the order of

allocate_memory calls or the order of free_memory calls.

However it would be incorrect to call the free_memory on the same pointer

twice without allocate_memory in between, like this:

void *ptr = allocate_memory(size);

free_memory(ptr);

free_memory(ptr);

And of course it would be incorrect to call free_memory on a pointer that

wasn’t previously returned from allocate_memory:

int *array = allocate_memory(size * sizeof(int));

free_memory(&array[2]);

Though it’s not of fundamental importance, I would allow calling free_memory

on NULL pointer any number of times even without a matching

allocate_memory.

Implementation constraints

Later in this post I will cover more constraints that have to be considered

by a particular implementation. However there is one important constraint to

keep in mind, and it’s that aside from the memory provided via

add_memory_pool the implemetation is only allowed to use \(O(1)\) of

additional memory.

You can think of this limitation in the following way. We are allowed to

create a few fixed global variables for our algorithm implementation outside

of the memory provided to the allocator via add_memory_pool, but any

unbounded memory that the implementation needs has to come from one of the

memory pools given to the algorithm.

That constraints makes a lot of sense and basically tells us that our dynamic memory allocation algorithm cannot depend on another dynamic memory allocation algorithm being available already.

Simple algorithm

Let’s move to the actual memory allocation algorithm. I will consider a few variations in this post, but all of them will be similar in a way and might be considered one algorithm with a few improvements on top.

The basic idea is that we are going to maintain a linked list of free memory ranges available. Each node of the list will describe a contigous free memory range.

This way the allocation essentially boils down to going through the list and finding a large enough free memory range. Naturally, it may happen that the memory range we find will be too large, so to avoid wasting memory we would need to split the memory range in a couple of memory ranges.

Freeing previously allocated memory range then essentially involves adding the freed range back to the free ranges list.

The linked list nodes themselves will be stored in the same memory pool we will allocate the memory from. And we need one global variable to store the head of the linked list.

That’s the general idea of the algorithm, however the devil is in details. To see where the problems may come from let’s look how one particular implementation of the algorithm may behave. In order to do that let me first introduce a few definition to use the same language:

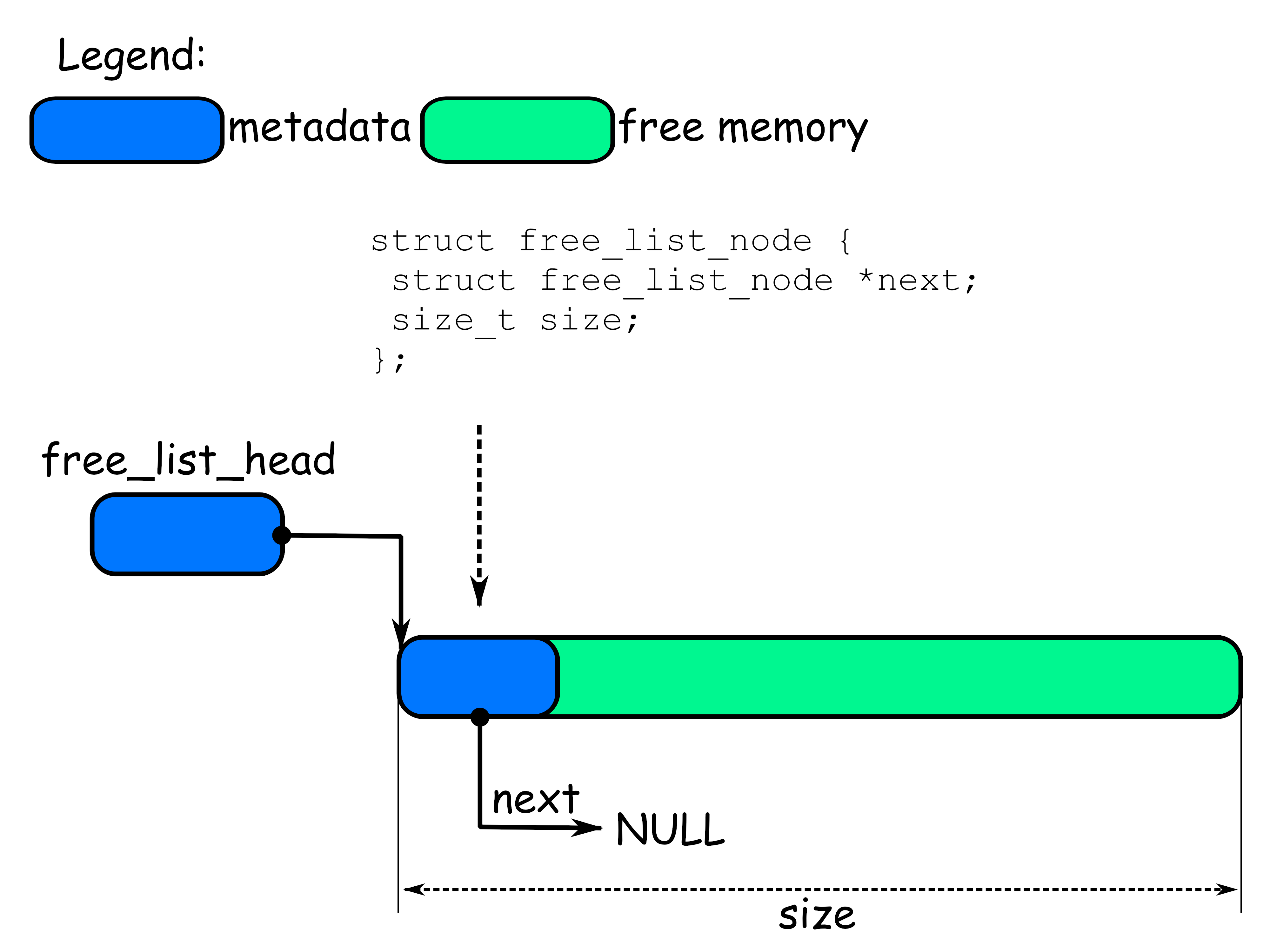

struct free_list_node {

struct free_list_node *next;

size_t size;

};

static struct free_list_node *free_list_head;

Here struct free_list_node describes one contigouse free memory range. I

will arrange those structure into a linked list, so I have to store the

pointer to the next range in the structure and that’s what the next field

is for. The global variable free_list_head points to the first element of

the list.

For each free memory range we need to know where it begins and how bit it’s.

I will store the struct free_list_node describing the free memory range at

the beginning of that range, so the pointer to the struct free_list_node

will also serve as a pointer to the beginning of the free memory range itself.

The size of the free memory range is described by the size field of the

struct free_list_node. There are multiple roughly equivalent ways to define

the size. Here I will take that size field includes the size of

struct free_list_node and all the memory in the range coming after that.

The following picture clarifies the definitions I use and shows how the pieces fit together:

On the picture I have only one free memory range. That’s how the state will

look like right after we called add_memory_pool once. The allocator

basically has one contigous free memory range and that’s it.

The free_list_head points to the only range we have at this point, so the

picture has an arrow from free_list_head to the beginning of the range.

At the beginning of the range we have struct free_list_node. It’s the

metadata that we maintain for our algorithm and I generally will denote the

metadata using blue bubbles on the pictures.

It’s important to note that struct free_list_node is stored right inside the

free range. Remember that we cannot use an unbounded amount of memory for our

metadata outside the given memory pool. And potentially we can have the

unbounded number of the free memory ranges in our algorithm.

Finally, since we have only one free range the next field of the

struct free_list_node contains NULL and that’s what the picture shows.

Let’s take a look at what will change when we allocate some memory.

NOTE: in the pictures below I will not show the details of the

struct free_list_nodein order to make them more compact. I use different colors to mark various structures in memory, so pay attention to the legend on the pictures.

Allocation

As was outlined before the allocation boils down to going through the list of free ranges until we find a large enough or reach the end of the list. Traversing the linked list is not really complicated, but there is one thing to keep in mind - to remove an element from a singly linked list you need access to the previous element in the list.

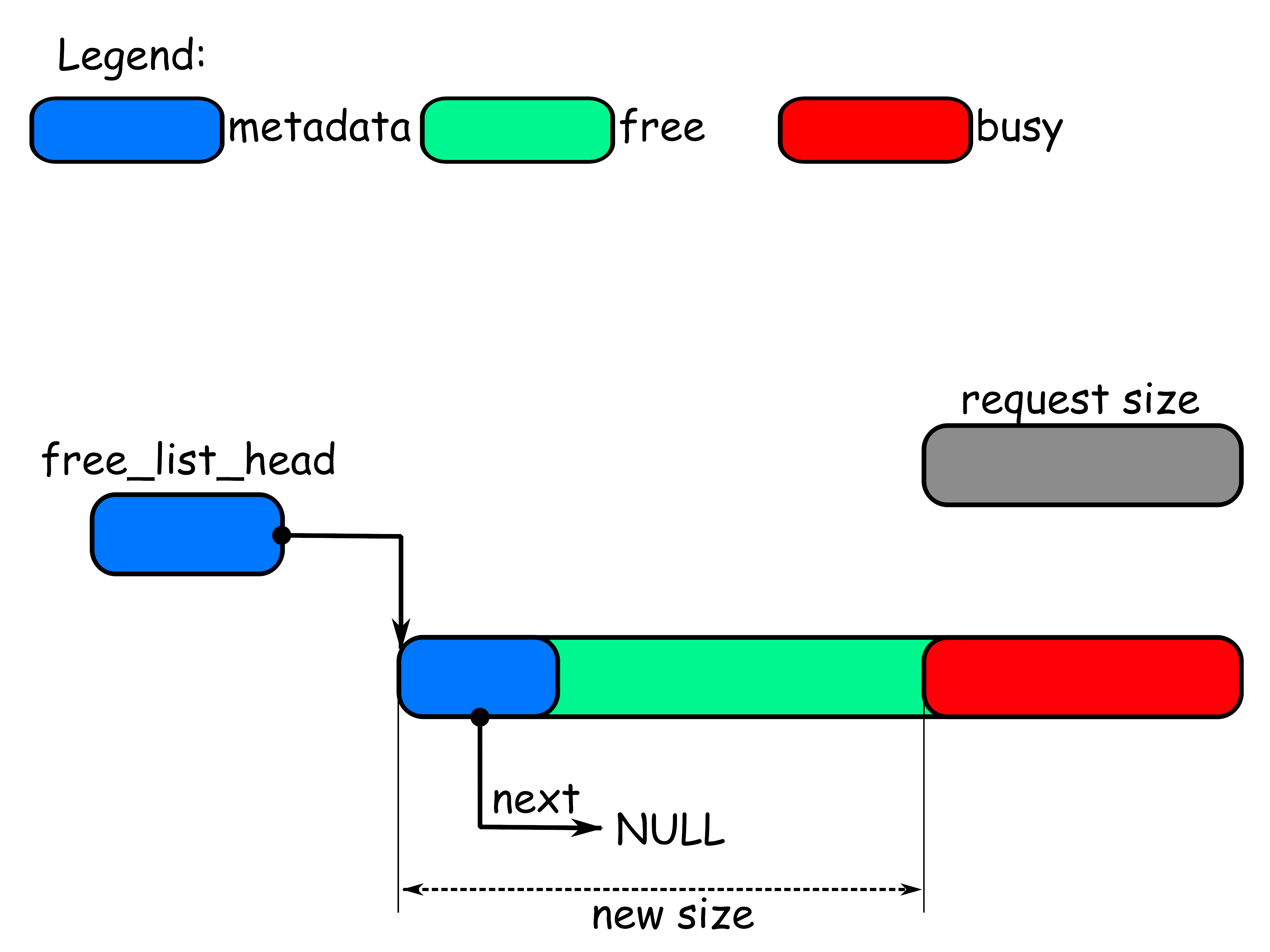

Now, let’s assume that we went through the list and found a large enough element (and also the element before that one). There are actually a couple of cases that we need to consider.

The problem is that the free range that we found might be to big for the requested size of the allocation. Say you found a 1MiB free range when you were asked to allocate just 8 bytes. Returning the whole range in this case would be a waste of memory (not to mention, that in order to do that we don’t really need any fancy algorithms).

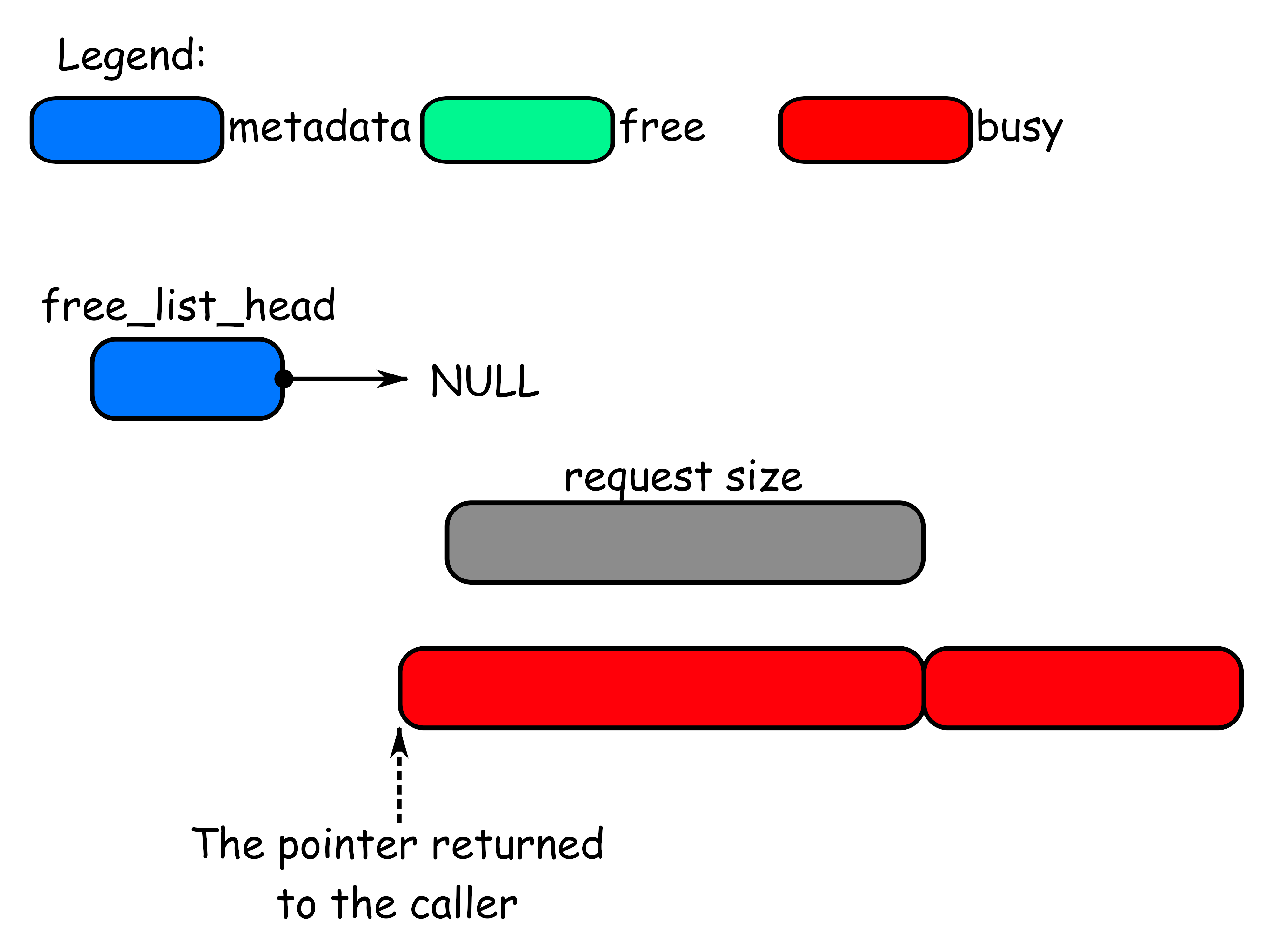

So what you might want to do is to cut off just enough memory from the found free range and return that part back to the caller. In other words, you might want to split the range you found in two. It might look like this:

On the picture above the tail of the free range is returned to the caller and

the head of the free range stays in the free list range. It allows for a simple

implementation that doesn’t require manipulations with the structure of the

free list. All it takes is to just update the size field and that’s it.

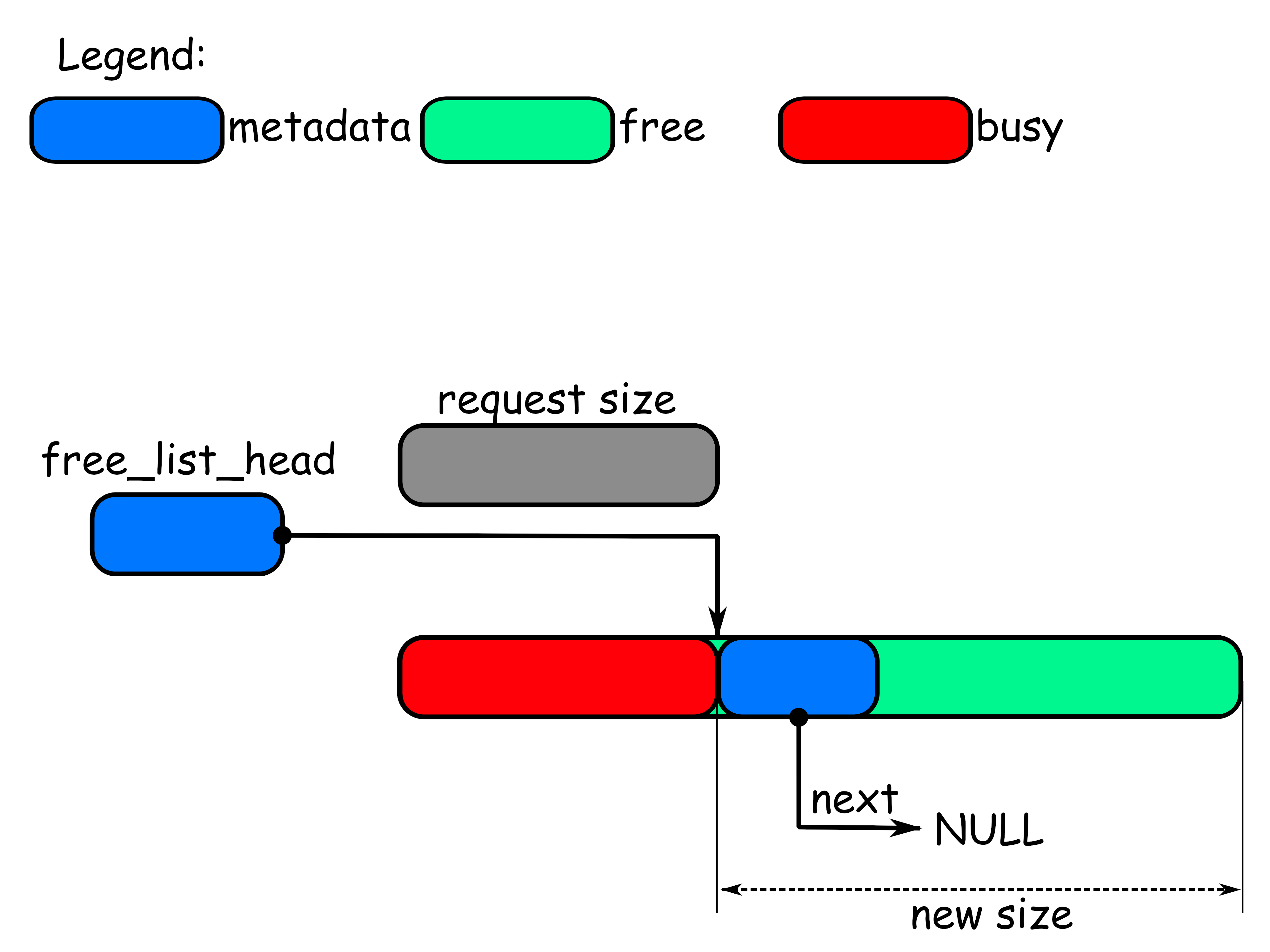

It’s possible to implement it differently and return to the caller the head of the free range and return to the free list the tail of the range as shown on the picture below:

The implementation of the second option is slightly more complicated, but there is a case to be made for that implementation as well. I will not elaborate on that here, since it’s not even the final version of the algorithm.

That was one case that we have to consider, what is the other case?

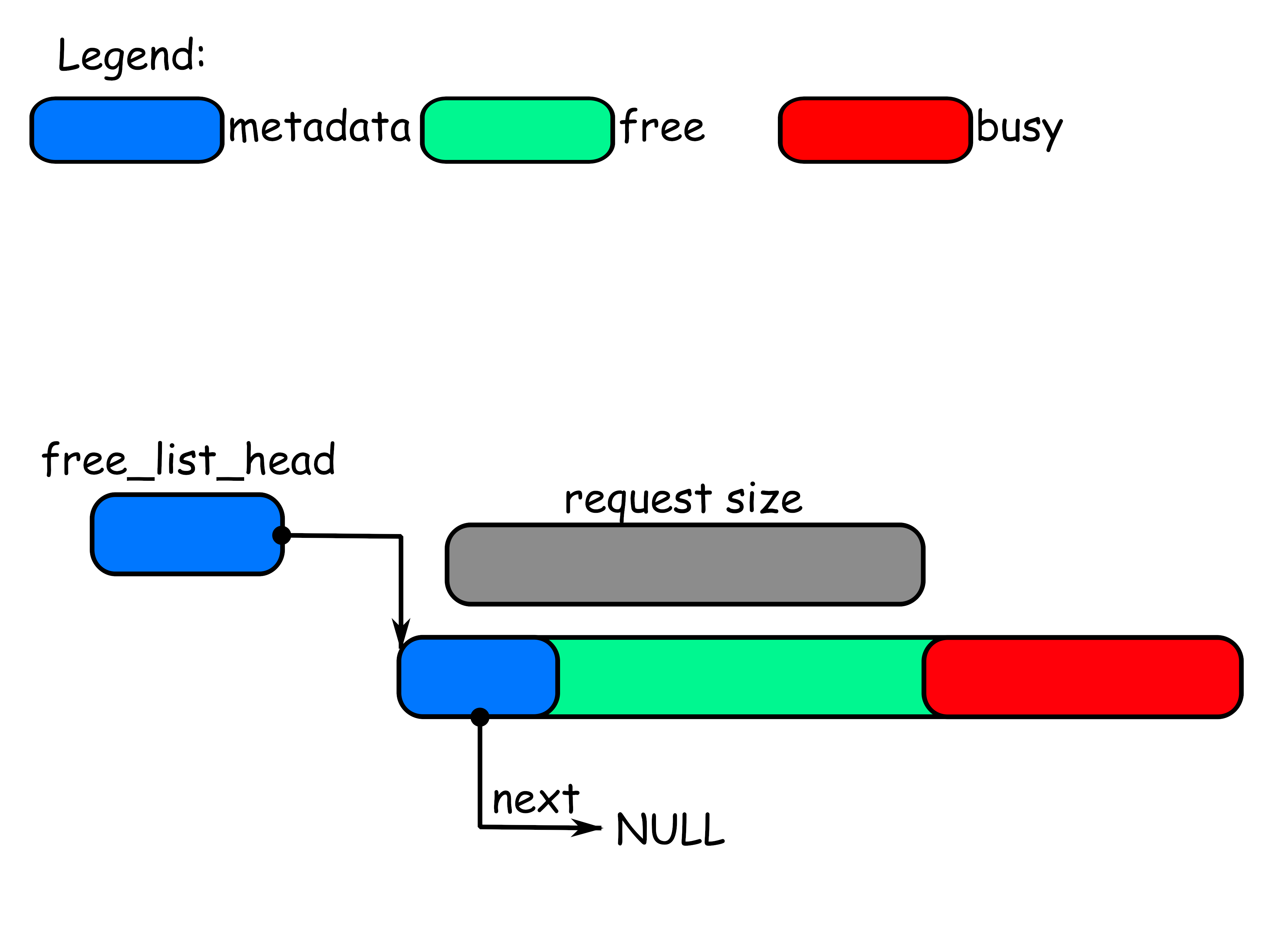

In the case I considered above I showed the request size with a gray bubble. Hopefully it was clear that the gray bubble in the previous case was much smaller than the size of the (only) available free range and that’s why we had to split it.

However, let’s now consider the case when the request size is much closer to the free range size we found for the allocation, as shown on this picture:

In this case we cannot split the free range in two as we did before because

the space that we will have left after returning one part of the range back to

the caller will be too small to store the struct free_list_node and therefore

we will not be able to add it to the list.

Fortunately, there is no requirement that we have to return the exact size the caller requested. We can return slightly more - that’s perfectly acceptable. It might look like a waste of memory and in a sense it’s. However the alternative might be even bigger waste if we cannot find the free range large enough to be split. If we only allow splitting free ranges in this case the allocation will fail and the memory will stay unusable anyways.

So all-in-all, we need to handle the case when we cannot split the free range we found in two. In this case we can remove the whole range from the list of the free ranges. After satisfing such an allocation request we will end up in the state shown on the picture below:

In the toy example on the pictures we allocated all the memory with just two allocation requests. In practice there might be many more requests required to exhaust all the memory.

However to get some intution of the aglorithm even a toy example is enough. The example should give you an idea of two cases that we need to consider:

- when we can split the free range we found

- when we cannot split the free range we found.

This example also should give you an idea of the initial state (when we have one contigous free range of memory) and the “end state”, when we allocated all the available memory.

Pedantic readers may say that it’s not an accurate presentation of the algorithm and that would be true, but again that’s not the final algorithm, so I’m cutting some corners.

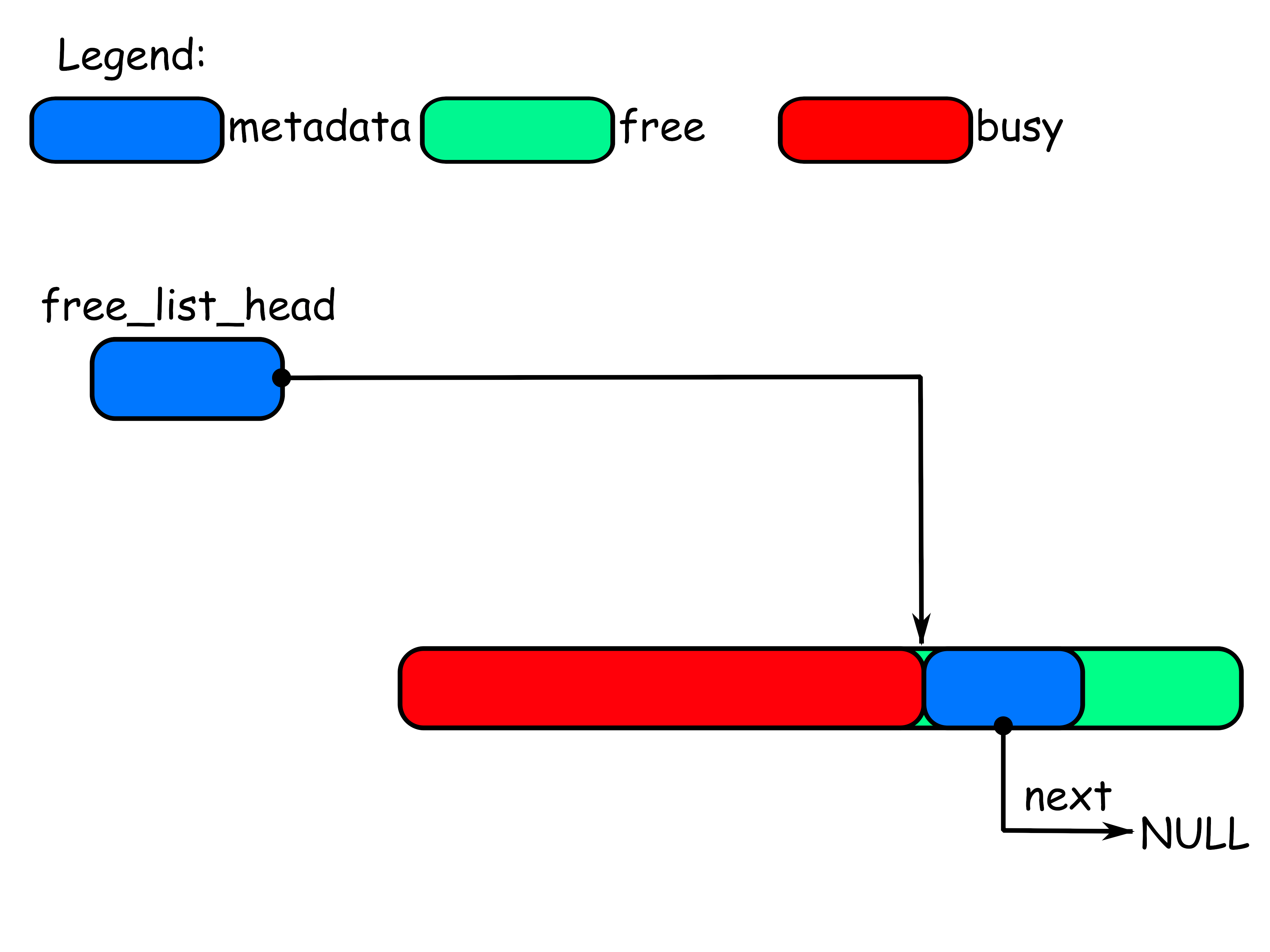

Freeing

In the example above we saw two allocations, now let’s consider the reverse operation of freeing previous allocated memory. Let’s start from freeing the first range that was allocated.

free_memory operation takes as a parameter the pointer that allocate_memory

previously returned. I briefly alluded that it should be possible to find out

the actual size of the freed region from just the pointer, so here I assume

that the size of the freed region is known as well.

NOTE: Don’t worry, I will show the actual implementation of this trick below, so for now let’s just assume that we indeed know the size of the freed region.

The basic logic of the free_memory operation is that we need to initialize

the struct free_list_node at the beginning of the range and add it to the

free list that free_list_head points to.

So in the end after the operation has been completed the state should look similar to the one shown on the picture below:

Unlike with the alloca_memory, free_memory operation doesn’t really have

multiple cases that needs to be considered. One thing worth mentioning though

is that to be able to initialize struct free_list_node at the beginning of

the freed memory range, this memory range must be large enough. It’s the same

constrain that I covered when we considered allocation operation above.

This puts an additional limitation on the allocation operation - we cannot

allocate regions that are smaller than sizeof(struct free_list_node).

Otherwise it would not be possible to perform the free_memory operation

later.

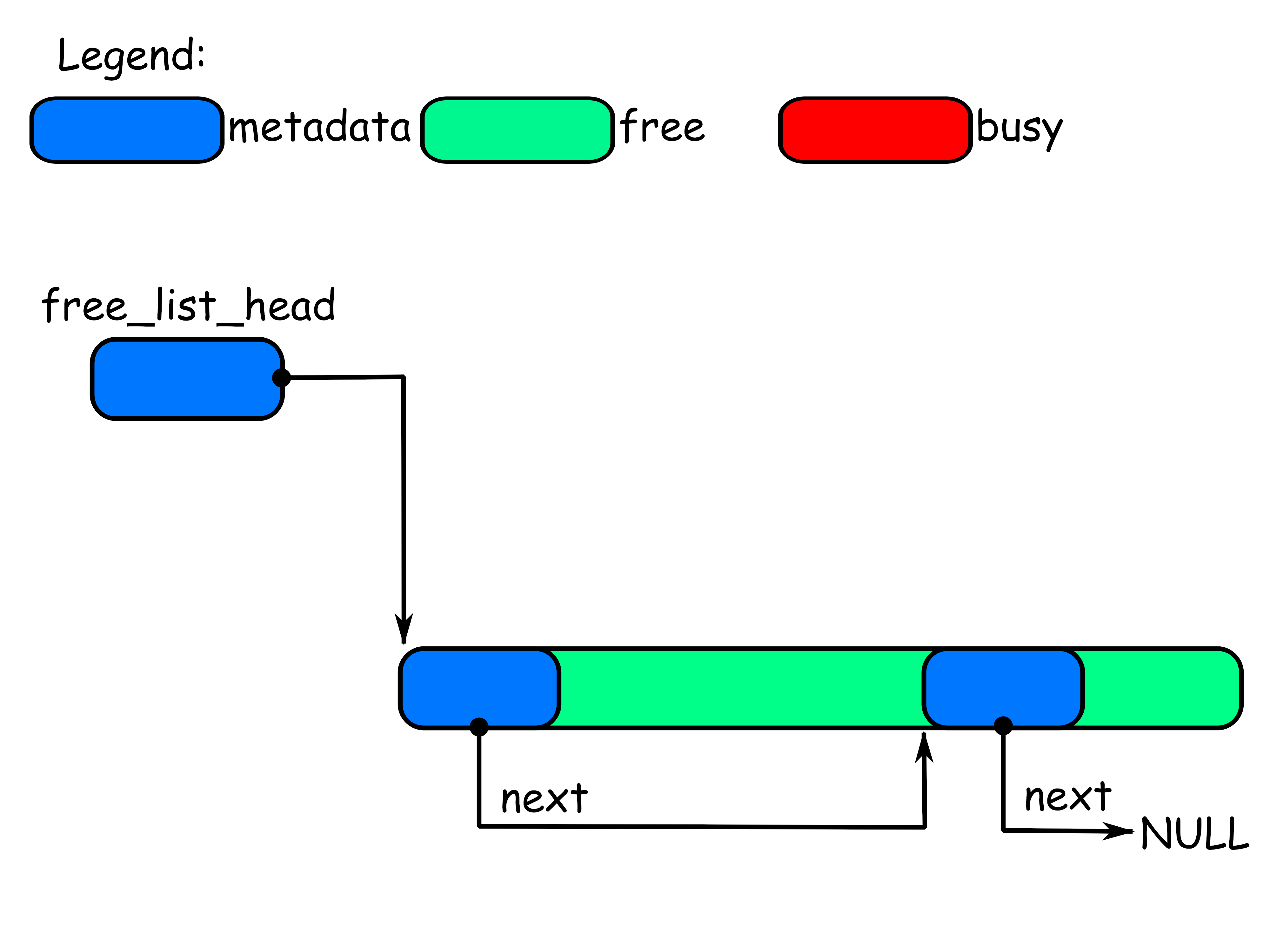

Let’s now look at the state after we free the second region of memory:

The freed region was just added at the beginning of the free ranges list. It was added at the beginning because it’s the simplest thing to do.

Some thoughts

So what can we learn from this rather informal example?

Since we are looking at the algorithms here it’s worth considering the complexity of the solution. As you can see the potential runtime complexity of the allocation depends on the size of the free list and is \(O(n)\), where \(n\) is the size of the list.

Sometimes we can find a large enough free range without scanning the whole list, but it’s not guaranteed. And in the worst case to discover that there isn’t any large enough regions we have to go through the whole list. So we probably would like to keep the list as short as possible.

The complexity of the freeing function is \(O(1)\), so we cannot really improve on that. That however also means that if we modify our algorithm we have plenty of room to make it worse.

Another observation that can be made is that we started the example with one big free region, but after freeing all the memory we allocated we ended up with two smaller regions of memory. So as it the algorithm was shown so far regions of memory can gradually get smaller and smaller in size.

That has at least two downsides. One of them is that it makes the list of free ranges longer. And as was noted above the size of the list directly affects the allocation runtime complexity.

The other downside is that it limits the ability to allocate large contigous ranges of memory. There is no guarantee that the allocator has enough memory to satisfy the request to begin with, but in our case the problem is that even when we in fact have large enough free contigous memory range it may happen that it was split in multiple smaller regions and we still cannot satisfy the request and that’s problematic.

Finally, in the shown example, the free ranges in the final free list ended up to be sorted by the starting addresses. It’s worth noting that’s it’s a pure coincedence. Consider for example the case when the same regions are freed in the different order.

Merging free memory ranges

As was shows above idenfinitely splitting memory ranges is problematic. So I now will consider how the neighbor free ranges can be joined together in bigger free memory ranges when possible.

There are quite a few options to choose from. For example, we can maintain the free ranges in the list ordered by the starting address. This way, when we free a memory range, we, using the sorting property, can find its neighbours and check if they are free. If the neighbors are free they can be joined together in one big free range.

There are multiple options to maintain free ranges ordered. For example, we can use an ordered data structure instead of a linked list. Some kind of a balanced binary search tree (AVL, RB, Splay, Treap, etc) would do the trick.

Using balanced search tree, in a way, will not affect the runtime complexity

of the allocate_memory operation. It’s still \(O(n)\) from the number of

elements in the tree, however it will help us to reduce the number of ranges

we have to consider, so it’s not exactly aples to aples comparision.

When it comes to the free_memory operation it’s pretty clear that we will

see a degradation from \(O(1)\) to \(O(log n)\) or worse depending on the

selected structure. It’s degradation no matter how you look at it, even if you

consider that \(n\) is smaller.

Alternatively, instead of mantaining free memory ranges ordered we could just

scan through the free ranges in the free_memory operation and find the free

neighbor memory ranges if they are in the list. Compared to an ordered search

tree it’s clearly a degradation from \(O(log n)\) to \(O(n)\).

Can we do better than a ordered search tree?

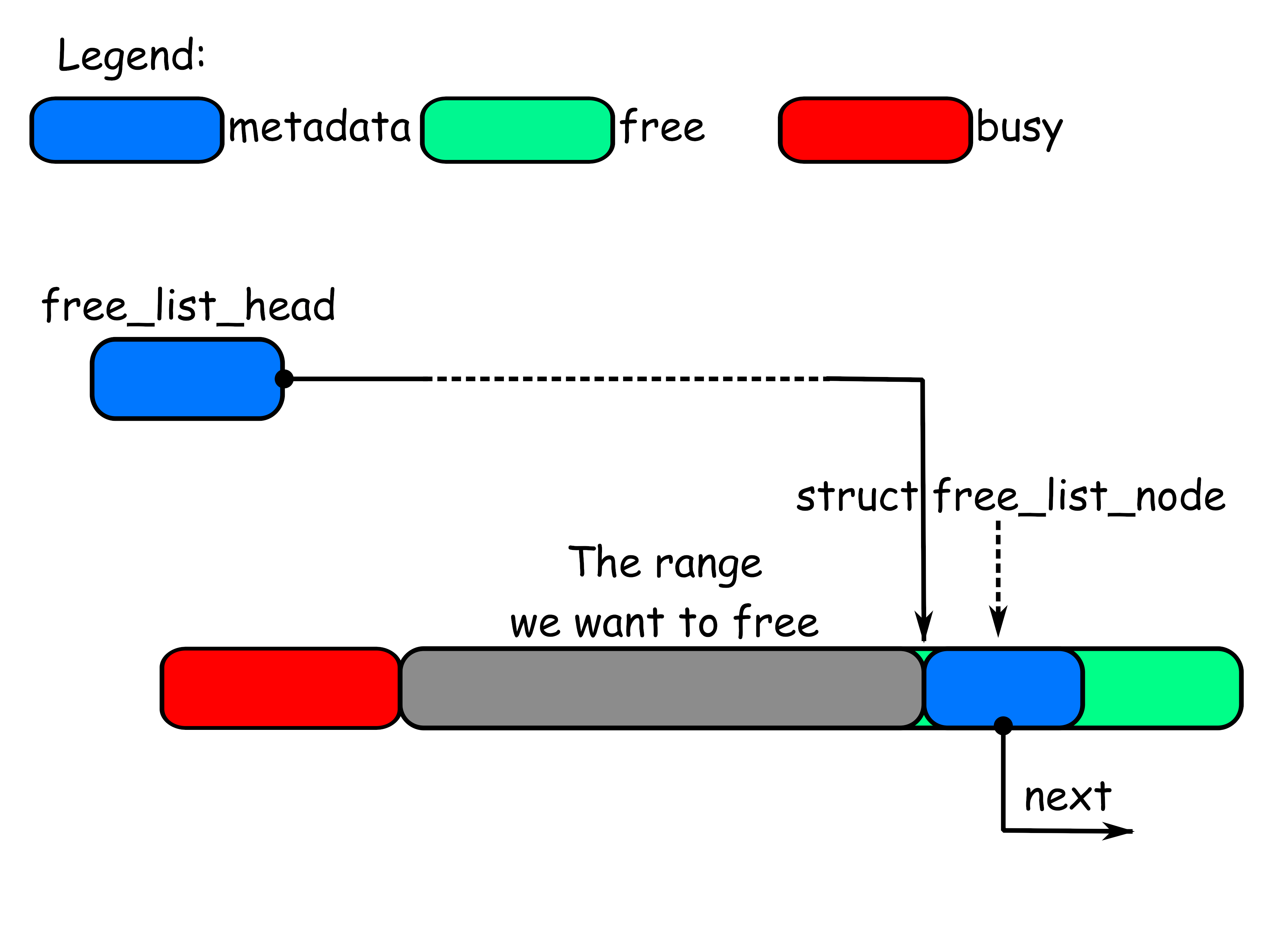

The key observation

So far we only kept track of the free memory ranges because that was the only thing we needed. All the allocated memory ranges were not recorded in the metadata in any way.

At the beginning of each free memory range we store a structure that I

previously called struct free_list_node, however there was no such thing for

the allocated memory ranges.

Returning back to the problem of finding neighbor free ranges we had to search

for the ranges in the list of free nodes. However, if the next range in memory,

after the one we are actually trying to free, is already free, then at the very

beginning it must have the struct free_list_node:

This gives us an easy way to get the pointer to the struct free_list_node of

the next range quickly without looking at the free list/tree at all. Let’s say

we are freeing a range of size size that begins at address addr. Then the

address of the struct free_list_node of the next range in memory is just

\(addr + size\) - a simple arithmetic operation.

However, this trick only works for the next range, but not for the previous

one, since there is no way for us to know the size of the previous range to

find where it begins and, therefore, the struct free_list_node.

To make the matters worse it also only works if the next range is free,

otherwise whatever pointer we get this way will not point to a valid

struct free_list_node.

And that gives us an important clue. What if we could fix our memory layout in such a way that free and allocated memory range always have some kind of a helper structure both at the beginning and at the end.

This structure must provide us with the information about the size of the range and whether it’s free or not. It might look something like this:

// We put this structure at the beginning of each memory range (free or busy).

// From the pointer to the header we can find a corresponding struct footer

// using simple arithmetic operations with the pointer to the header,

// header::size field and size of the struct footer.

struct header {

struct header *next;

size_t size;

bool free;

};

// We put this structure at the end of each memory range (free or busy).

// Similarly, from the pointer to the footer we can find a corresponding struct

// header using just simple arithmetic on the pointer to the footer,

// footer::size field and the size of the struct footer.

struct footer {

size_t size;

bool free;

};

That will allow us to find neighborhood ranges and check if they are free in \(O(1)\). In order to merge the free ranges together however we also should be able to remove them from the free list.

Unfortunately removing elements from a singly linked list requires updating the previous element in the list and to find the previous element in the free list we will have to scan it from the beginning.

That kills all the benefits of our observation and also gives us a clue how to fix the problem: where singly linked list is not enough, doubly linked list will do the trick.

If instead of a singly linked list of free ranges we will maintain the doubly linked list instead we will be able to remove an element from the list by having just the pointer to the element we want to remove in \(O(1)\).

Implementation

We now have all the basics for an algorithm that avoids the kinds of memory fragmentation that we discussed above and at the same time has the same runtime complexity:

- \(O(n)\) for

allocate_memory, wherenis the number of contigous free memory ranges available to the allocator - \(O(1)\) for

free_memory.

Let’s take a look in a little bit more details at the implementation.

Doubly linked lists

I want to start with some helper structures and functions. As discussed the algorithm requires the use of doubly linked lists, so let’s cover them since the implementation of the linked list can be rather generic and separate from the the allocator algorithm itself.

Here I will implement doubly linked list with a dummy head node - a quirky long name. Let’s break it down piece by piece.

First of all it’s a doubly linked list. That would mean that each node in the list will somehow point to the previous and the next node in the list. That’s the important property that allows us to delete a node from the list in \(O(1)\) by having just the pointer to the list.

NOTE: I should probably say that the operation is not removing the node from the list, but removing the node from a list (whatever list it belongs to if at all).

Here is how the structure describing the node of a doubly linked list might look:

struct list_node {

struct list_node *next;

struct list_node *prev;

};

To understand the part about the dummy head node it might be useful to consider what problems we might face when working with doubly linked lists and with linked lists in general.

A node of double linked list as was mentioned above contains pointers to the next and previous elements in the list. However there are some corner cases that needs to be considered - what if in the list there is no previous and/or next element.

Dealing with such corner cases is quite cumbersome and error prone, so it makes sense to exercise a bit of engineering lazyness and consider how those corner cases can be avoided.

One way to avoid corner cases is to make sure that the list always contains at

least one element. Then we can link the next pointer of the last node of the

list to point to the first element of the list. Similarly we can link the

prev pointer of the first node in the list to point to the last node of the

list.

To achieve that we can introduce a dummy element that is always in the list:

struct list_head {

struct list_node head;

};

// Link the dummy head node to point to itself

void setup_empty_list(struct list_head *head)

{

head->head.next = &head->head;

head->head.prev = &head->head;

}

When traversing the list we naturally will have to skip this dummy element, but that’s quite easy to do. In return our list operations become quite simple because they don’t need to deal with all the corner cases.

Now all we need need is to define a couple of function:

- a function to remove a node from the list

- a function to add a node to the list.

Removing an element from the list is quite simple now:

void list_remove(struct list_node *node)

{

struct list_node *prev = node->prev;

struct list_node *next = node->next;

prev->next = next;

next->prev = prev;

}

Similarly adding a node to the list is not complicated at all:

void list_add_after(struct list_node *prev, struct list_node *node)

{

struct list_node *next = prev->next;

node->prev = prev;

node->next = next;

prev->next = node;

next->prev = node;

}

Linked lists as defined here cannot store any data, however since I’m giving example in C language we can use some dirty tricks to circumvent this limitation, I will show you what I mean by that further down.

Data Alignment

Before we move any further it’s worth stepping back for a second to look at one practical limitation for dynamic memory allocation. You see, with the current problem statement, when we allocate memory we have no idea what this memory is allocated for.

For example, it can be allocated to store one-byte character strings, an array of floating point numbers or an array of structures. Those structures themselves can contain strings, numbers, other structures, etc.

Why does it matter what we store in the dynamically allocated memory? Well, what we store there tells us how the data will be accessed. For example, if you store one-byte character strings in that data, then you likely will access it one byte at a time. On the other hand if you’ll store an array of double precision floating point numbers there, then you will be accessing it eight-bytes at a time.

And here is where we might see a potential problem. The modern hardware memory has a simple interface. You give processor an address and it fetches content of the memory at that address - nithing really complicated. However at the same time the hardware memory has complicated layered implementation:

- there is the memory itself

- there is some memory controller that handles read/write operations

- there are multiple levels of caches separating the processor and the memory itself.

Caches typically cannot work with arbitrary memory chunks. Typically, the cache would operate in fixed size blocks often referred to as cache lines. Of course, the size of the cache line depends on the specific hardware, but to give you an idea the size of the cache line is on order of few tens of bytes, like 32 bytes or 64 bytes.

Besides that, to make things even more complicated, each cache line can only store data from certain memory addresses. For example, if the cache line is 32 bytes long it can only store data from addresses aligned to the 32-byte boundary.

NOTE: When we say that the address is aligned on the boundary

Xit means that the address must be equal to 0 by moduloX: \(addr \equiv 0 \left(mod X\right)\).

Why am I talking about that? Imagine if you’re accessing an 8-byte long value that crosses the boundary between two cache lines. In this case instead of actually loading just one cache line from memory to the cache you’d need to load two neighbor cache lines for just that one 8-byte long value. So accessing badly aligned data might be less effective.

Some architectures can go as far as to forbid unaligned accesses all together. Typically it comes in a form of natural alignment requirement. For example, if you want to access data in one 8-byte read or write operation then the address of the data must be aligned on the 8 bytes boundary, similarly for 4-byte long accesses the data have to be aligned on the 4 bytes boundary, etc.

If we don’t know how the data will be accessed we have to return the data that is aligned to the largest boundary that makes sense. Further in this post I will assume that the largest alignment that makes sense is 8 bytes and will consider that in my implementation.

The 8 bytes is not completely arbirary and it’s enough for many use-cases, however there are known use cases where this boundary is not enough.

Maybe a better solution for this problem is to change our interface slightly

and take the require alignment as an argument of the ‘allocate_memory’

function. While it makes sense it also pushes part of responsibility on the

caller of the allocate_memory. Besides that the allocate_memory and

free_memory is the interface that is commonly used in practice (for better or

worse), so I stick to it in the introductionary post like this.

It’s not all bad, using the allocate_memory and free_memory interface as it

was described above you can also implement a memory allocation routine that

will take the alignment as an argument. So the presented interface is not

really that limiting.

Header and Footer

Now let’s return to the implementation of the memory allocation algorithm. Above I’ve already presented how the header and footer of memory ranges may look in general, now let’s adjust them to use doubly linked lists:

struct header {

struct list_node link;

size_t size;

bool free;

};

struct footer {

size_t size;

bool free;

};

Note how I’ve put the struct list_node described above at the beginning of

the struct header. This guarantees that that pointer to the link field

will match the pointer to the struct header that this field belongs to.

That allows us to use this type-unsafe trick to convert from the

struct list_node pointer to the struct header pointer:

struct list_node *link_ptr = /* something */;

struct header *header_ptr = (struct header *)link_ptr;

Since both pointers actually contain the same value all we need is to change

the type. Naturally, it’s not a generally safe trick, so for this to work

correctly you need to know for sure that the pointer to struct list_node

actually points to the link field inside some struct header instance.

NOTE: If you feel bad about such type-unsafe tricks don’t be. The way the problem is stated there is no way to avoid it. You are starting with a range of untyped memory to begin with, so some type usafe convertions have to happen at some point if you want to store any kind of structure inside this memory.

Now, let’s introduce a few helper functions to manipulate struct header and

struct footer pointers. I will start from introducing a few helper function

to perform alignment:

uint64_t align_down(uint64_t addr, uint64_t align)

{

return addr & ~(align - 1);

}

uint64_t align_up(uint64_t addr, uint64_t align)

{

return align_down(addr + align - 1, align);

}

Both functions assume that align argument contains a power of two. It might

seem as not a particularly generic solution, but the matter of the fact is that

most of the time alignment requirements are powers of two.

With that out of the way, we need to be able to perform a few operations with

header and footer. We need to be able to find the header of the next

memory range in memory by the footer of the previous one:

struct header *next_header(struct footer *footer)

{

uint64_t addr = align_up((uint64_t)footer + sizeof(*footer), ALIGNMENT);

return (struct header *)addr;

}

The opposite operation, finding the footer of the previous range in memory by

the header is also needed:

struct footer *prev_footer(struct header *header)

{

uint64_t addr = align_down(

(uint64_t)header - sizeof(struct footer), ALIGNMENT);

return (struct footer *)addr;

}

Both implementation above make sure that the pointers they return are properly

aligned to the ALIGNMENT, which as I mentioned before is 8 bytes.

There are another two useful operations with header and footer that we will

need. Those are finding header of the memory range having a footer of that

range and vice versa:

struct header *matching_header(struct footer *footer)

{

uint64_t addr = align_up(

(uint64_t)footer + sizeof(*footer), ALIGNMENT) - footer->size;

return (struct header *)addr;

}

struct footer *matching_footer(struct header *header)

{

uint64_t addr = align_down(

(uint64_t)header + header->size - sizeof(struct footer),

ALIGNMENT);

return (struct footer *)addr;

}

And on this note we are done with the operations on headers and footers. Let’s

move to the implementation of the add_memory_pool.

add_memory_pool

When implementing add_memory_pool we will have to perform some safety checks

on the given memory range. I will skip those for simplicity and will just

assume that the given memory range is properly aligned and big enough to be of

any use.

Additionally, our algorithm depends on begin able to access the header and

the footer structures of the memeory ranges located next in memory. That

creates a possibility of a corner case. What if the range we are working with

is at the beginning or at the end of the memory pool. In this case there will

be no next or no previous memory range.

I’m dealing with this problem by inserting fake footer at the beginning and

header at the end of each memory pool added using add_memory_pool. The size

stored there is not important, but free must contain false. This way I

guarantee that there is always the next footer or the previous header.

Let’s see how it works:

// This is the head of our free list, we need to initialize it properly before

// begin able to use it.

static struct list_head free;

static void setup_free_list()

{

if (free.head.next == NULL && free.head.prev == NULL) {

free.head.next = &free.head;

free.head.prev = &free.head;

}

}

void add_memory_pool(void *begin, void *end)

{

const size_t metasz =

align_up(sizeof(struct header), ALIGNMENT)

+ align_up(sizeof(struct footer), ALIGNMENT);

struct header *header = NULL;

struct footer *footer = NULL;

struct header *dummy_header = NULL;

struct footer *dummy_footer = NULL;

// First make sure that the free list has been properly initialized

setup_free_list();

// We put a fake footer at the beginning of the range and mark it as busy

// so every time we look at it we would think that the previous memory

// range is busy.

dummy_footer = (struct footer *)begin;

dummy_footer->free = false;

// Similarly we put a fake header at the end.

dummy_header = (struct header *)align_down(

(uint64_t)end - sizeof(*dummy_header), ALIGNMENT);

dummy_header->free = false;

// Besides the fake header and footer we also need to create actual header

// and footer for the free memory range we will add to the pool.

header = next_header(dummy_footer);

footer = prev_footer(dummy_header);

header->free = true;

header->size = (uint64_t)end - (uint64_t)begin - metasz;

footer->free = true;

footer->size = header->size;

list_add_after(&free.head, &header->link);

}

Now we know how to add new memory ranges to the memory allocator. The

implementation might look somewhat complicated, but it basically just

initializes a couple of struct header and struct footer structures and

that’s it. All the complexity comes from the address arithmetics.

allocate_memory

Before we look at the actual allocation implementation let’s introduce another

helper function. A function that given struct header returns a pointer to the

data that can be used:

static void *data_pointer(struct header *header)

{

uint64_t addr = align_up((uint64_t)header + sizeof(*header), ALIGNMENT);

return (void *)addr;

}

You see we cannot just return a pointer to the struct header for the caller

to use. If they overwrite the content of struct header we created our

algorithm will not work as it depends on it. So instead we need to return a

pointer pointing after the struct header.

Another way to look at it is that allocation request for size bytes actually

allocated size bytes plus whatever memory we need to store struct footer

and struct header.

Now when that is out of the way let’s take a look at the actual allocation:

void *allocate_memory(size_t size)

{

const size_t metasz =

align_up(sizeof(struct header), ALIGNMENT)

+ align_up(sizeof(struct footer), ALIGNMENT);

const size_t minsz = metasz + ALIGNMENT;

struct list_node *head = &free.head;

// We adjust the allocation size to be ALIGNMENT bytes aligned, to keep

// everything aligned.

size = align_up(size, ALIGNMENT);

for (struct list_node *ptr = head->next; ptr != head; ptr = ptr->next) {

struct header *header = (struct header *)ptr;

struct footer *footer = matching_footer(header);

struct header *new_header = NULL;

struct footer *new_footer = NULL;

// The range is too small to serve the request. We need at least size

// bytes plus memory requires for the footer and header.

if (header->size < size + metasz)

continue;

// We have two cases to consider: one when we can split the range in

// two and another when the range is too small to be split. This is

// the second case, when we cannot split the range. In this case we

// remove it from the free list and return the whole range to the

// caller.

if (header->size < size + metasz + minsz) {

list_remove(&header->link);

header->free = false;

header->free = false;

return data_pointer(header);

}

// The following code handles the case when the range can be split in

// two. I'm returning the caller the tail of the range and the head

// stays in the free list, but with the reduced range size.

// Firstly reduce the size of the free range and create an appropriate

// footer, since the footer will have to move to a different place when

// the size changes.

header->size -= size + metasz;

footer = matching_footer(header);

footer->size = header->size;

footer->free = true;

// Secondly we create a new header and footer for the tail of the range

// that will be returned to the caller.

new_header = next_header(footer);

new_header->size = size + metasz;

new_header->free = false;

new_footer = matching_footer(new_header);

new_footer->size = new_header->size;

new_footer->free = false;

return data_pointer(new_header);

}

// If we didn't find any suitable range then we return NULL as an indicator

// of a failure.

return NULL;

}

The implementation is long, but not really complicated. It’s just a few dozens

of lines of code and most of those are comments. All the magic will be

happening in the free_memory function however, so let’s move to it.

free_memory

Again we will start the free_memory implementation with introduction of a

helper function that performs an operation opposite to the data_pointer

function introduced above.

You see the free_memory function takes a pointer we returned to the user as

an argument. We don’t care about the pointer and want struct header pointer

instead. That’s where all the relavant information is stored, including the

size of the allocated range:

static struct header *data_header(void *ptr)

{

uint64_t addr = align_down(

(uint64_t)ptr - sizeof(struct header), ALIGNMENT);

return (struct header *)addr;

}

And now the actual implementation of the free_memory function:

void free_memory(void *ptr)

{

struct header *header = data_header(ptr);

struct footer *footer = matching_footer(header);

// Footer and header of the neighbor memory ranges

struct footer *prev = prev_footer(header);

struct header *next = next_header(footer);

// If the range in memory next to the one we are freeing is also free then

// we can merge them together. This branch handles this merging logic.

if (next->free) {

struct footer *next_footer = matching_footer(next);

// We need to remove the next memory range from the list of free ranges

// and add it's memory to the one we are freeing. Since we change the

// size by attaching to the end of the range the footer pointer changes

// as well.

list_remove(&next->link);

header->size += next->size;

footer = next_footer;

footer->size = header->size;

}

// This branch handles the case when the previous range in memory is free

// and therefore have to be joined together with the region we are freeing.

// The logic is very simmetrical to the case above.

if (prev->free) {

struct header *prev_header = matching_header(prev);

list_remove(&prev_header->link);

prev_header->size += header->size;

header = prev_header;

footer->size = header->size;

}

// We merged all the ranges together and now it's time to mark the whole

// range free and add it to the list of the free ranges.

header->free = true;

footer->free = true;

list_add_after(&free.head, &header->link);

}

And that’s it. We have a working implementation of a rather generic memory allocator.

Concurrency

Now when we have a complete implementation let’s take another step back and look at a few other practical aspects that are of importance for a real dynamic memory allocator that were not considered yet.

One of them is concurrency. It’s not a supririse that many programs nowadays benefit from hardware concurrency for performance and from preemtive multitasking for other reasons (like creating responsive graphical user interfaces).

All-in-all, concurrency is important and the implementation above cannot serve

concurrent allocate_memory and free_memory requests correctly. Naturally

there is a variety of ways to adjust the implementation to handle concurrency.

Probably the simplest way is to guard allocate_memory, free_memory and

add_memory_pool operations with a mutex. That definitely will address the

correctness concern. However such a solution to an extent will loose the

benefits that concurrency provides, so it’s worth at least considering

alternatives.

Another approach is to maintain multiple independent allocators, say one allocator per thread. So far the implementation depended on the global state, but it doesn’t have to be the case. We can change the interface a little bit to take an allocator structure as a parameter of all the functions.

This way we can have multiple truly independent operations. However if the threads have to share data between each other we might still have a problem and require mutexes to protect allocators.

For example, we have to handle a case when a memory range was allocated in one thread and then freed in another. In this case multiple threads will have to use the same memory allocator (the thread that frees a memory range have to free it using the same allocator the range was allocated from).

Best-fit vs First-fit

In the implementation above I allocated memory from the first free range large enough to handle the request. That’s not the only possibility. After all, since the allocation requires traversing the list anyways, we can consider preferring one range over another when serving allocation requests.

The strategy the presented implementation used is called, unsurprisingly, first-fit strategy. There is another strategy commonly discussed in the literature called best-fit.

The best-fit strategy requires finding the minimum free range in the list that can serve the allocation request. Intuitively this approach might sound appealing as it avoids splitting large memory ranges in smaller ones when it’s not necessary, thus it might seem that it should reduce the memory fragmentation.

In practice however depending on the application and the load on the dynamic memory allocator best-fit may or may not be better than the first-fit. So you need to be careful with applying intution to complicated random systems. To scare you even more, Prof. Donald Knuth in the first volume of “The Art of Computer Programming” presents the results of Monte Carlo simulations comparing best-fit and first-fit strategies, comes to the conclusion that in all the experiments he conducted the first-fit strategy performed better.

Optimizations

While there is very little we can do to improve the runtime complexity of the presented algorithm, there are some optimizations that were shown to actually work in practice. One rather simple one is easy to understand intuitively and so I’m presenting it to you here.

The runtime complexity of the allocation alogrithm is determined by the time

it takes to scan through the free list until we find a large enough free range.

Let’s say that most of the time we have to skip X first entries in the list

until we find the large enough range. If the X is large enough the allocation

will be slow.

On the other hand if we consistently have to skip X entries at the beggining

of the list it means that they are likely too small to satisfy most of the

allocation requests.

When we decide on whether we want to split the free memory range or returning the whole range to the caller in the implementation above I used the following criteria:

if (header->size < size + metasz + minsz) {

/* return the whole range to the caller */

}

The criteria was based on the limitations of the algorithm mostly. We cannot

split the range if the part we will return to the free list is not small enough

to contain the header, the footer and also have enough memory to satisfy the

minimum possible allocation, which in our case was ALIGNMENT bytes.

We can actually increase the threshold used in this criteria to avoid addint to the list ranges that are unlikely to be big enough to satisfy an allocation request. That should improve the peformance at the cost of spending more memory.

That’s one way to deal with a pathalogical case I outlined above. However there

is another rather simple way. If most of the time we have to skip X entries

at the beginning of the list, let’s just do it once and remember the position in

the list where we stopped the last time when we successfually allocated memory.

There is no way to over and over skip small ranges at the beginning of the list if we can do it once and remember where we stopped. For the next allocation we can start not from the beginning of the list, but from the position we stopped at the last time.

Implementing this trick requires some care since a free_memory call may

invalidate the position we remembered in the last allocate_memory call,

however since this trick is only for runtime optimization it’s easy to detect

inside the free_memory function if the operation is going to affect the

rememebered position in the free list and reset it in \(O(1)\) time.

Instead of conclusion

There are a few things worth mentioning to the reader who might consider checking the repository.

First of all on GitHub the

implementation of the memory allocator lives in bootstrap/alloc.h and

bootstrap/alloc.c if you ever want to read the code.

Also, in the implementation on GitHub I use slightly different names for the functions and provide a few more additional functions that are not covered in this post and are not essential for the algorithm.

Aside from that I’d like to share a few thoughts on the algorithm itself. It’s worth asking if the end algorithm is good and whether the end implementation is good?

Well, they are better then even more simplistic approach that the one I started this post with, so it’s clearly not the worst possible algorithm, but that’s a low bar.

One way to look at whether the algorithm and implementation are good is whether they serve their purporse. If the pruporse of the memory allocation in your case is a simple, not a performance critical memory allocator for a relatively small amount of memory, then this algorithm is good enough. That’s however isn’t a particularly high bar either.

Another way to look at whether the alogirthm and implementation are good is to ask if there is anything better. And the answer to this is a resounding yes. There are much better dynamic memory allocation algorithms at least in terms of performance and I’d want to cover some of them in one of the future posts.

tags: algorithms - dynamic-memory-allocation